One summer, I waged a war with my best friend over a famous book about friendship. It wasn’t the content of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novel that divided us but how we proved that we loved it. We did so the way we have since our teens: logging page-count progress, leaving pithy reviews, and reading theories from strangers, all on Goodreads. I felt clever and motivated and anxious, but ultimately an arbitrary pressure clouded the actual words on the page — I had to wonder: What was I reading for anymore?

The secondary social engagement is entangled with the actual act of reading, for me and 125 million other people. Since its launch in 2007, the “world’s largest site for readers” has transformed the consumption of books. Right now, book sales in the U.S. are the highest they’ve ever been. A prolonged period of forced isolation is one proposed cause; so is the rise in easy content creation (meaning #BookTok). There’s a desire stirring in our culture, both in reaction to the digitization of life and in line with the trendy factor that digital platforms foster, to be seen as someone who reads overshadowing the reading itself.

The Jeff Bezos-owned site can be an ugly place to be. Beige in every sense of the word, the aesthetics have essentially been unchanged since Amazon’s 2013 acquisition of Goodreads. A San Francisco couple initially built it for their friends to compare the popularity of Dune versus Pride and Prejudice. Now, ads for Prime shows splash on the home page. The algorithm gives Ferrante fans links to textbooks in Italian.

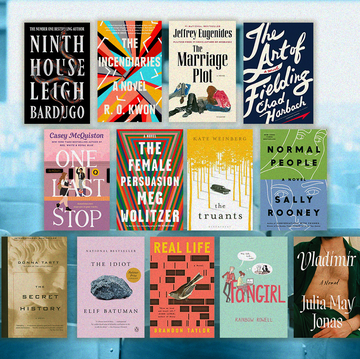

Books have a certain place on all the other platforms. Twitter records the dramas of dropped book deals and controversial author takes, but can also be a place for writers to find an audience. TikTok turns self-published titles into bestsellers after enough tearful front-camera reviews. Instagram can venerate the book as a visual object and intellectual status symbol. It is there, most glaringly, that reading is not for personal pleasure or edification but is instead for image-building. On Goodreads, these uses mingle. I watch, and I am watched — by best friends and by Facebook friends from middle school — but I also catalog, reflect, and ideate. The site is a tool, an encyclopedia. “Goodreads is almost a separate interest from reading,” says Emma, the site’s second-most-popular reviewer. She does not reveal her face or full name online, though she does show off her color-coded bookshelf. “I get satisfaction from marking a book as ‘read,’ from finding a book I want to read, from commenting back and forth on a review of a book with someone who’s also read it.” She’s been in a three-year-long text conversation with Stephen, another top reviewer, about Sally Rooney’s Conversations With Friends. For him, “half the fun in reading a book now is getting to review it.”

Reading for pleasure teeters between private indulgence and social practice. It always has — Socratic circles in ancient Greece, serialized novels released in Victorian-era newspapers, and book clubs of all kinds suggest pleasure in the discourse. The concept of satisfaction feels newer, and better fits into what Jia Tolentino defined as the “optimized” life, where technology allows us to maximize our potential for capital. Influencers recommend listening to audiobooks at 1.5 times the speed, and multiple Goodreads users told me they deliberately pick up shorter books to achieve certain goals.

Every year, participation in Goodreads’ reading challenge climbs. Four million people pledged to read a certain number of books in 2018, with an average goal of 61 titles. About 16 percent met theirs. In 2022, almost 7 million people spent their year reading with a number in mind. Incorporating metrics-based incentives is classic gamification. Take for example, the Duolingo bird’s happy face after a seven-day streak or the rings of your Apple watch closing when you walk 10,000 steps — these can oftentimes feel infantilizing but are psychologically effective. We’re more likely to complete tasks to get these rewards.

It’s a great thing that reading is on the rise. Screen dominance is a fact of modern life that structures all our other pleasures and leisures and is the reason we need a respite. “I want an hour of my life that’s not influenced by brands or marketing,” says avid reader Chamidae Ford, one member of a Brooklyn friend group I interviewed in which everyone is a Goodreads user. Last year, the reviewer Emma, who is 25, accomplished a lifelong goal of reading a book a day. “There’s no such thing as quantity over quality,” she insists, while explaining that she’s naturally speedy and needs just three hours to read the average novel. “I work remotely, and a lot of it was about being intentional in making time every day for something I’m passionate about. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do it.”

Internet culture reporter Kelsey Weekman was inspired by bloggers like Emma to “become a book person.” She’d read a few dozen buzzy books between 2017 and 2021. But in 2022, she tore through 390. By mid-May, she’d already made it to 200. She achieves such numbers by reading some six hours daily — before work, on her lunch break, as soon as she clocks out. “I’m a binge reader. Very obsessive, very intense. The same mindset that I used to have towards scrolling on the internet, I’ve replaced with books,” Weekman says. She’s off BookTok these days, but Goodreads prevails.

Weekman speaks about returning to reading with pure joy; Stephen loves books because they are “innately and beautifully human.” This is why Goodreads works: It’s built using “the labor of devotion,” an abstract mode of exploitation in which someone (in this case, the average Goodreads reviewer) does not make material gains from their work (their reviews and their clicks that translate to sellable data) and is unaware that they’re generating wealth for others (Amazon). Some reviewers receive advance copies or broker other deals with publishers, but the overwhelming majority of reviews are written by regular people. “Goodreads melds two traditionally feminized activities,” says media scholar Brooke Erin Duffy. “Leisure-time reading and community-oriented consumerism.”

The novel has been coded as feminine since the 18th century, when it was directly marketed to a new class of literate ladies of leisure. It is often also an exercise — I don’t disagree with Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard when he says that writing and reading are feminine because they require you to think about feelings. But what do feelings do for society? Readers have tantrums on fan sites about plot-line subtleties; they miss their train stop because they can’t look up from the page. The pressure to organize these feverish emotional impulses cogently — to turn poison into productive fuel — feels artificial. It feels like the opportunities to optimize are not in service of ourselves. The five-star rating system is quick and legible, but what’s the cost of the nuances lost?

Book discovery too got streamlined. When the goal is to consume a lot of books, it follows that it would be optimal to have a working list of ones to read. It would be optimal if you could find a book based on what you already liked enough to finish. It would be supremely optimal if there were a single button to order it on Amazon. Discovery used to be “a one-to-many network,” explains Christine Larson, Ph.D., who researches Amazon’s impact on book culture. You listened to the TV host, the newspaper columnist, or the bookseller behind a counter. The new model is many to many: Anyone can tell everyone what they’re reading.

“It’s become common practice to put a lot of energy into garnering reviews on Goodreads pre-publication so that the book is launched with a boost,” says Smith Publicity’s Olivia McCoy. “Reader reviews have a tremendous impact on purchasing behaviors from other readers and from bookstores.”

The inherent problem with this model was revealed this June, when Eat, Pray, Love’s Elizabeth Gilbert pulled her upcoming novel set in 20th-century Siberia from publication. A year before its release, it was already marred by hundreds of one-star reviews on Goodreads by people offended by the setting, given the current war in Ukraine. So-called Goodreads bombing is not criticism; it’s not even, I’d argue, about the literature. It’s a social media pile-on no different from the rest, a distracting drama that allows people to play important antagonists for the day.

By exerting influence and extracting attention, Goodreads is working exactly as it should. Amazon drags its feet in responding to fake reviews, review extortion, and the like, says Larson, because “they’re not incentivized to reduce clutter or problems. Their incentive is to sell ads. The harder it is to find what you’re looking for, the longer you’re on the site. Those few more seconds translate to dollars.”

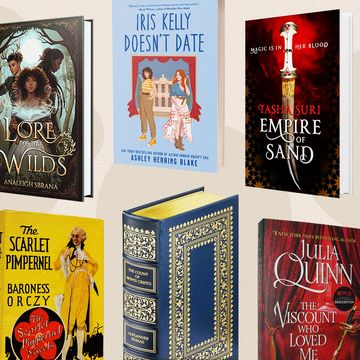

Some deserving authors have become financially successful from the “many to many” network. It was once much more isolating to be a genre reader, and harder to publish romance or horror or anything else stigmatized as lowbrow. Goodreads provides a place to gather and to prove that there’s interest in a queer sci-fi novella that seems, on the surface, niche. While publishers I talked to bristled at the suggestion that the site holds the power that the Gilbert drama suggests, it remains the easiest way to gauge non-industry feedback.

“Goodreads reviews are often nearsighted — like, ‘This didn’t meet my needs’ — in a way that doesn’t reflect on the quality of the book,” says Alex Manley, author of The New Masculinity. The reviews for a poetry collection they published in 2016 were mostly benign, except for one. “I finally had one negative review from a complete stranger with no platform to speak of, and it was very smart and was kind of a wake-up call. It made me want to be better as a writer.” At the same time, Manley says, “I think it can be potentially psychologically damaging, or bad for one’s practice, to spend too much time reading the comments. That’s something that every writer needs to figure out for themselves.”

I would argue that’s also true for every reader. I don’t want to lose the experience of reading a book I’d never heard of but found on a stoop, or rereading a book even if it doesn’t count toward an annual goal. I don’t want every book I read to be a mappable point in the fated conception of me and what other things I might like (to buy).

While Goodreads remains a behemoth, McCoy says it “has inspired the creation of indie review communities growing in popularity as a response to the anti-Amazon rhetoric.” One of the more reactionary is So Textual, started in early 2021. The $4-per-month digital members’ club gets you recommendations that “disregard the trendy in order to pay reverence to the classics, the canonical, the overlooked.” They seem to be speaking directly to the woman who’s sick of optimizing when they say, “We’re a digital platform with an analog mindset: We don’t recommend books beyond your capacity to actually read them.”

But this woman still relies on social technology, setting an Instagram time limit alert only to shoo it away. So Textual’s community is there, presenting a rigid aesthetic of “bookish women” as chic, neat, and expensive. Prettier than Goodreads, it repeats the strange effects of reading for pleasure in an age of digital surveillance, while claiming that it isn’t. I turn back to Ferrante in The Story of the Lost Child. “Perhaps Lila was right,” wonders narrator Elena. “My book — even though it was having so much success — really was bad, and this was because it was well organized, because it was written with obsessive care, because I hadn’t been able to imitate the disjointed, unaesthetic, illogical, shapeless banality of things.”

Perhaps I should try something: read a good, random book and tell no one.

Greta Rainbow is an arts and culture writer based in Brooklyn. Follow her on Twitter @gertsofficial.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY