The OpenAI Mess Is About One Big Thing

Corporate governance is playing a starring role in the chaos unfolding inside the world’s most famous AI start-up.

This is Work in Progress, a newsletter by Derek Thompson about work, technology, and how to solve some of America’s biggest problems. Sign up here to get it every week.

Updated at 11 a.m. ET on November 22, 2023

OpenAI, the famed artificial intelligence startup, has been wracked with chaos for the last six days. On Friday, the board of directors fired chief executive Sam Altman for “not being consistently candid.” On Sunday, under pressure from investor Microsoft, the firm brought Altman back to the office to discuss his rehiring, only to determine that, no, he was still very much fired. Early Monday morning, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella announced that Altman would join the tech giant in a new undefined role, only to back off that announcement in the following hours. Later on Monday, roughly 700 of the nearly 800 employees at OpenAI signed a letter demanding the return of Altman. Finally, on Tuesday, OpenAI announced that Altman would return to the company as chief executive. The key board members who fired him would either step down or leave the company entirely.

If this seems dizzying, the next bit might require Dramamine. Sutskever played the key role in firing Altman over Google Meet on Friday, then declined to rehire him on Sunday, and then signed the letter on Monday demanding the return of Altman and the firing of his own board-member co-conspirators. On X (formerly Twitter), Sutskever posted an apology to the entire company, writing, “I deeply regret my participation in the board’s actions.” Altman replied with three red hearts. One imagines Brutus, halfway through the stabbing of Caesar, pulling out the knife, offering Caesar some gauze, lightly stabbing him again, and then finally breaking down in apologetic tears and demanding that imperial doctors suture the stomach wound. (Soon after, in post-op, Caesar dispatches a courier to send Brutus a brief message inked on papyrus: “<3.”)

As a matter of human drama, the past few days most resemble a failed mutiny, in which a rebellion among the leadership initially ousts the captain, only for the counterinsurgency’s leaders to be ultimately tossed off the ship. But as a matter of corporate drama, the OpenAI fracas is above all a great example of why the incredibly boring-sounding term corporate governance is actually extremely important.

We still don’t know much about the OpenAI fracas. We don’t know a lot about Altman’s relationship (or lack thereof) with the board that fired him. We don’t know what Altman did in the days before his firing that made this drastic step seem unavoidable to the board. In fact, the board members who axed Altman have so far refused to elaborate on the precise cause of the firing. But here is what we know for sure: Altman’s ouster stemmed from the bizarre way that OpenAI is organized.

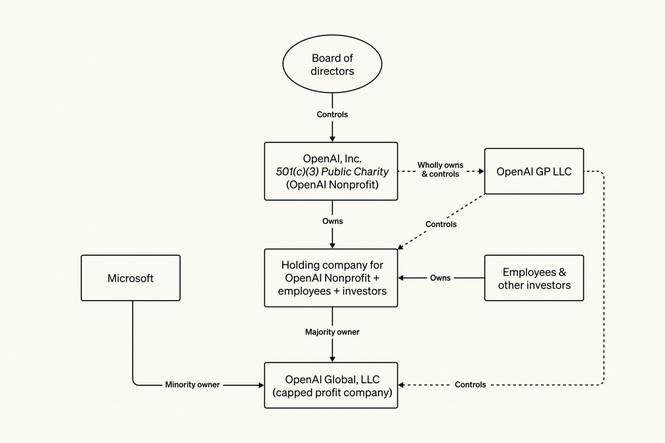

In the first sentence of this article, I told you that “on Friday, OpenAI fired its chief executive, Sam Altman.” Perhaps the most technically accurate way to put that would have been: “On Friday, the board of directors of the nonprofit entity of OpenAI, Inc., fired Sam Altman, who is most famous as the lead driver of its for-profit subsidiary, OpenAI Global LLC.” Confusing, right?

In 2015, Sam Altman, Elon Musk, and several other AI luminaries founded OpenAI as a nonprofit institution to build powerful artificial intelligence. The idea was that the most important technology in the history of humankind (as some claim) ought to “benefit humanity as a whole” rather than narrowly redound to the shareholders of a single firm. As Ross Andersen explained in an Atlantic feature this summer, they structured OpenAI as a nonprofit to be “unconstrained by a need to generate financial return.”

After several frustrating years, OpenAI realized that it needed money—a lot of money. The cost of computational power and engineering talent to build a digital superintelligence turned out to be astronomically high. Plus, Musk, who had been partly financing the organization’s operations, suddenly left the board in 2018 after a failed attempt to take over the firm. This left OpenAI with a gaping financial hole.

OpenAI therefore opened a for-profit subsidiary that would be nested under the OpenAI nonprofit. The entrepreneur and writer Sam Lessin called this structure a corporate “turducken,” referring to the dubious Thanksgiving entrée in which a cooked duck is stuffed inside a cooked turkey. In this turducken-esque arrangement, the original board would continue to “govern and oversee” all for-profit activities.

When OpenAI, the nonprofit, created OpenAI, the for-profit, nobody imagined what would come next: the ChatGPT boom. Internally, employees predicted that the rollout of the AI chatbot would be a minor event; the company referred to it as a “low-key research preview” that wasn’t likely to attract more than 100,000 users. Externally, the world went mad for ChatGPT. It became, by some measures, the fastest-growing consumer product in history, garnering more than 1 billion users.

Slowly, slowly, and then very quickly, OpenAI, the for-profit, became the star of the show. Altman pushed fast commercialization, and he needed even more money to make that possible. In the past few years, Microsoft has committed more than $10 billion to OpenAI in direct cash and in credits to use its data and cloud services. But unlike a typical corporate arrangement, where being a major investor might guarantee a seat or two on the board of directors, Microsoft’s investments got them nothing. OpenAI’s operating agreement states without ambiguity, “Microsoft has no board seat and no control.” Today, OpenAI’s corporate structure—according to OpenAI itself—looks like this.

In theory, this arrangement was supposed to guarantee morality plus money. The morality flowed from the nonprofit board of directors. The money flowed from Microsoft, the second biggest company in the world, which has lots of cash and resources to help OpenAI achieve its mission of building a general superintelligence.

But rather than align OpenAI’s commercial and ethical missions, this organizational structure created a house divided against itself. On Friday, this conflict played out in vivid color. Altman, the techno-optimist bent on commercialization, lost out to Sutskever, the Brutus-cum-mad-scientist fearful that super-smart AI poses an existential risk to humanity. This was shocking. But from an organizational standpoint, it wasn’t surprising. A for-profit start-up rapidly developing technology hand in glove with Microsoft was nested under an all-powerful nonprofit board that believed it was duty-bound to resist rapid development of AI and Big Tech alliances. That does not make any sense.

Everything is obvious in retrospect, especially failure, and I don’t want to pretend that I saw any of this coming. I don’t think anybody saw this coming. Microsoft’s investments accrued over many years. ChatGPT grew over many months. That all of this would blow up without any warning was inconceivable.

But that’s the thing about technology. Despite manifestos that claim that the annunciation of tech is a matter of cosmic inevitability, technology is, for now, made by people—flawed people, who may be brilliant and sometimes clueless, who change their mind and then change their mind again. Before we build an artificial general intelligence to create progress without people, we need dependable ways to organize people to work together to build complex things within complex systems. The term for that idea is corporate structure.

OpenAI is on the precipice of self-destruction because, in its attempt to build an ethically pristine institution to protect a possible superintelligence, it built just another instrument of minority control, in which a small number of nonemployees had the power to fire its chief executive in an instant.

In AI research, there is something called the “alignment problem.” When we engineer an artificial intelligence, we ought to make sure that the machine has the intentions and values of its architects. Oddly, the architects of OpenAI created an institution that is catastrophically unaligned, in which the board of directors and the chief executive are essentially running two incompatibly different companies within the same firm. Last week, the biggest question in technology was whether we might live long enough to see humans invent aligned superintelligence. Today, the more appropriate question is: Will we live long enough to see AI’s architects invent a technology for aligning themselves?