The Man Who Raced to Tell the World That Mount Everest Had Been Climbed

When Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary made history by reaching the summit, a courier named Ten Tsewang Sherpa ran 200 miles to Kathmandu to deliver the news. He died a few weeks later. His story has never been told—until now.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

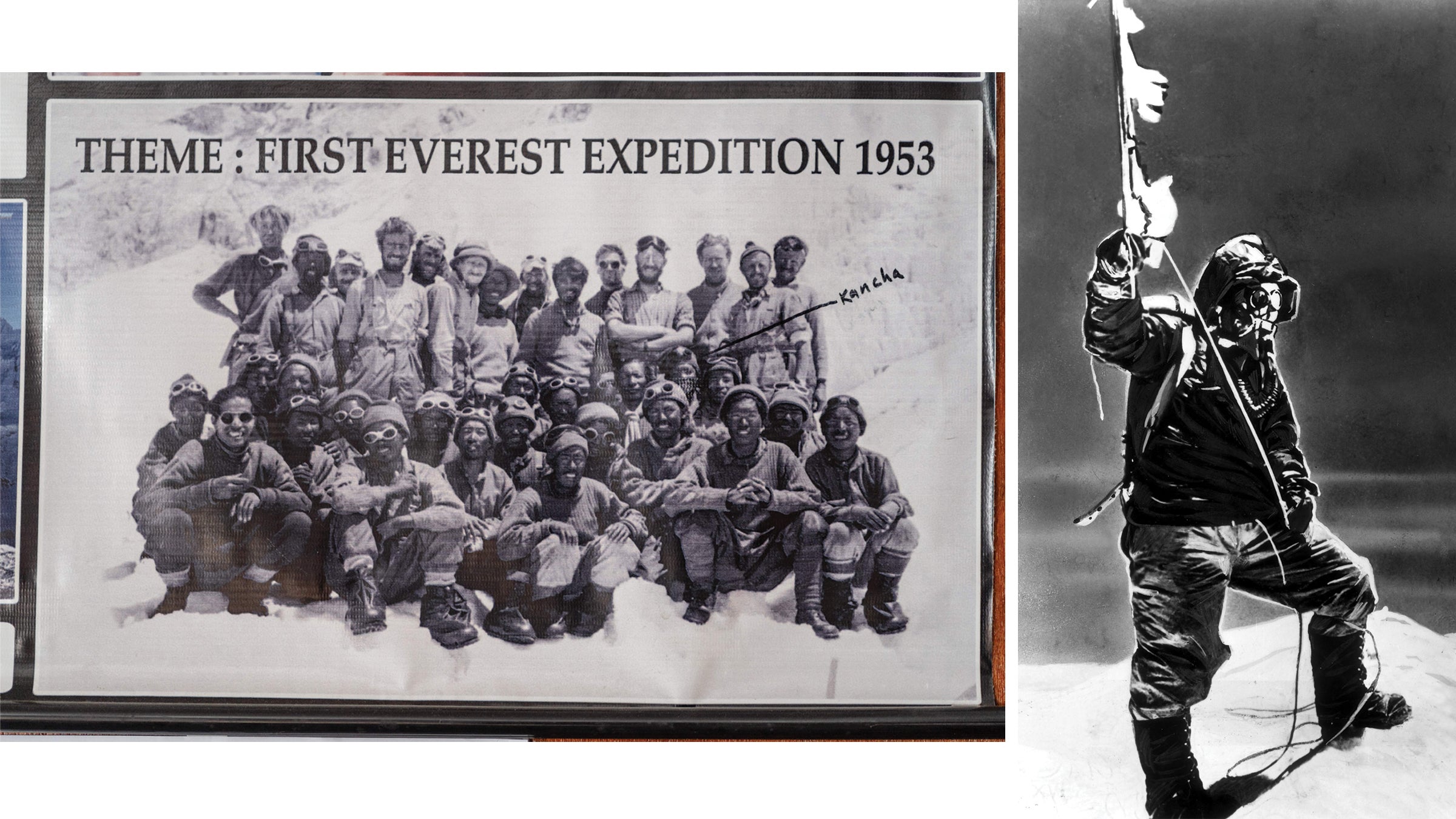

By the time Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hillary reached the summit of Mount Everest in May of 1953, the British had been trying to climb it for 31 years. This was the country’s ninth expedition, in addition to two reconnaissance flyovers commissioned by England’s wealthy elite in the 1930s. Meanwhile, several other countries had been trying to find their way to the summit at 29,035 feet, continually threatening to grab the prize away from the Crown.

In 1947, a rogue Canadian engineer named Earl Denman got to 22,000 feet before being turned back by a storm. In 1951, Denmark’s Klaus Becker-Larsen made it to the North Col—a 23,000-foot ridge on the Tibet side of the mountain—but turned back because of rockfall. In 1952, a Swiss expedition failed to make the summit, perhaps only because their Sherpas got nervous about the weather and the expedition leaders were too polite to push them on. If the 1953 British expedition was unsuccessful, France had the permits in hand to try next.

You can’t really overstate how badly England needed this. Over the previous decade, a yearslong World War II bombing campaign—the Blitz—had destroyed over a million British homes, and the cost of victory put a damper on the economy that lasted for years. In the summer of 1947, British control over India came to an end, resulting in widespread violence and massive loss of life. A few years later, in early 1952, their wartime king, George VI, died suddenly, a few months after undergoing an operation for lung cancer. In short, England was taking some lumps, and the nation was looking for something to celebrate. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II coincided nicely with Everest’s climbing season.

So when Tenzing and Hillary reached the summit at 11:30 A.M. on May 29, their feat was a source of pride for the whole empire. Britain had proved itself Great. And as the climbers descended, the race was on to tell the world.

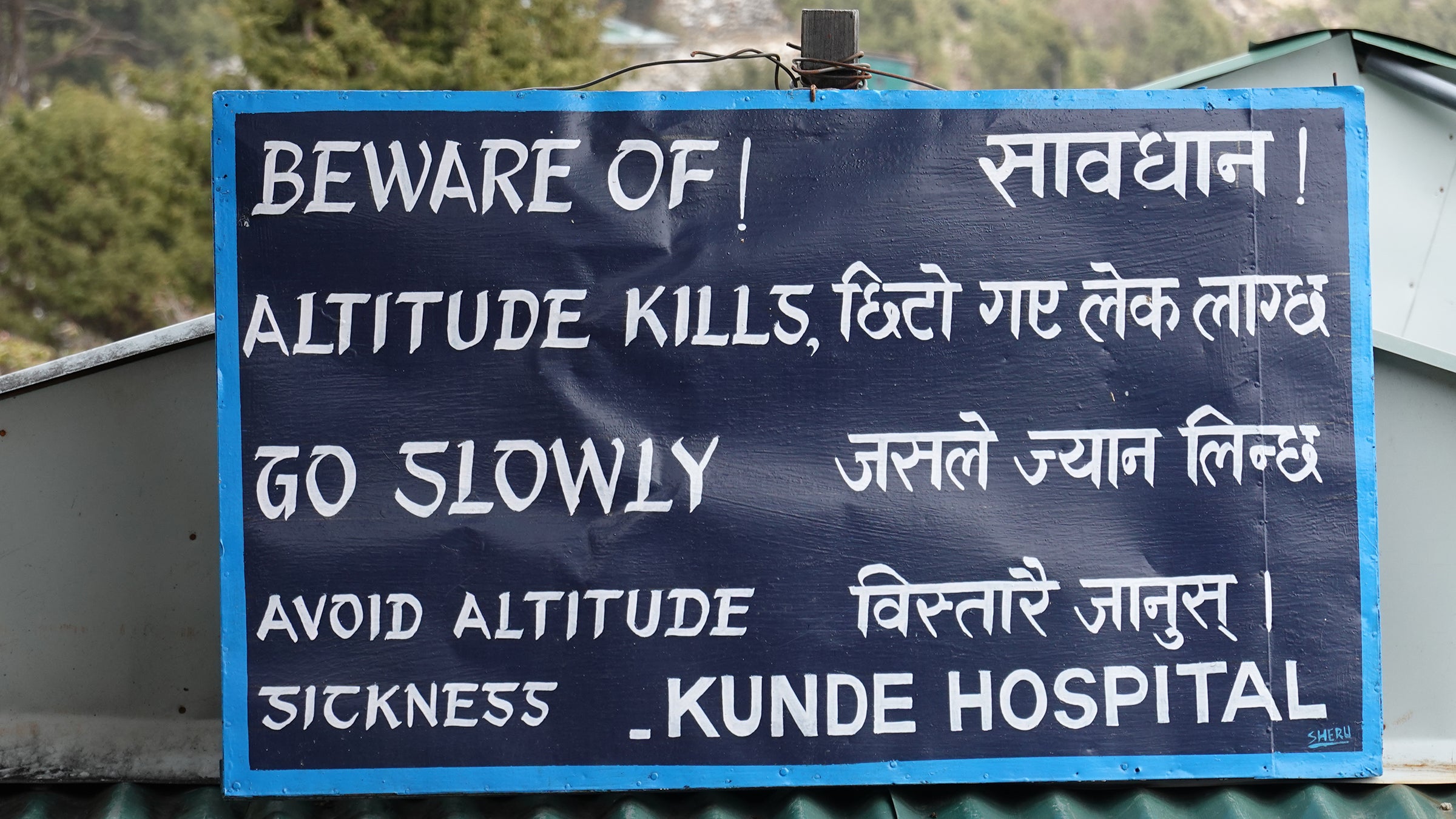

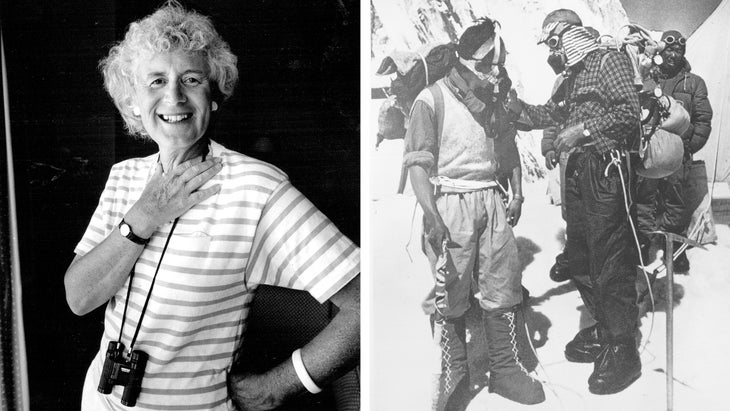

James Morris, a London Times reporter, was embedded with the expedition and had been waiting at a high camp—21,000 feet—for news of success or failure. (Morris underwent a gender transition in the 1970s and took the name Jan Morris.) It was hours before she got word, at which point Morris rushed down toward Base Camp in gathering darkness. When she got there, her only means of communication were the mail runners—a half-dozen trusted Sherpas who carried updates from the expedition 200 miles from Base Camp to Kathmandu. There had never been bigger news to deliver.

But this is where the story gets fuzzy, imprecise, and very nearly lost. Because there’s almost no record of what happened on that run to Kathmandu. And a few weeks after the message arrived, the runner who carried it was dead.