Google and Microsoft make some of the most-used software in the world. They’re also deeply committed, financially and narratively, to AI. Microsoft is by far the largest investor in OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, and has comprehensive access to its technology. Google is responsible for a lot of the foundational research that makes “generative AI” possible and has spent billions developing tools of its own. Both have been trying to figure out how to actually deploy AI in the products that make them money, and they’re trying all sorts of things.

Google is testing out auto-summarized searches and tools for writing emails and documents. Microsoft has built tools to speed up programming tasks. Each has shown off tools that purport to streamline work-related tasks — transcribing meetings; manipulating data in spreadsheets; and generating or editing text, images, presentations, and videos — bringing automation to bear on routine productivity tasks. You can expect to run into a lot of this sort of stuff soon, if you haven’t already, in the form of little buttons and prompts offering shortcuts: Summarize this; generate that.

But Microsoft and Google — along with many others — have converged on another way to build AI into all their products to which they’re ready to subject approximately the entire computer-using public: chatbots.

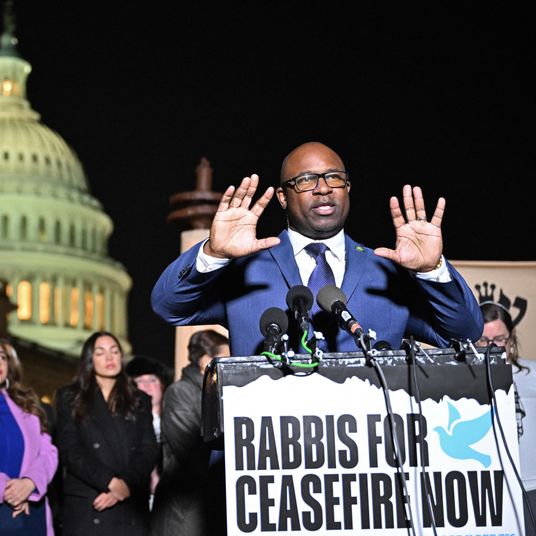

Early this week, Google announced Bard Extensions, which let users access their Gmail, Google Docs, and Google Drive data through a chat interface; Maps and YouTube will be accessible via chat as well. On Thursday, Microsoft announced a collection of tools called CoPilot for Windows, which has users chatting, in natural language, with their computers.

It’s conceptually obvious enough. Large language models are good at generating text and also at interpreting it. In the way early graphical interfaces automated complicated text commands, the thinking goes, computers that can simply listen — and be told plainly what to do — might automate clicking, scrolling, typing, and more. Software is suddenly much better at extracting intent from written or spoken text, so sure: It’s time to put chat interfaces everywhere. It’s time to stop using your computer and start telling your computer what to do.

Google and Microsoft know this is more possible, now. What they don’t yet know is whether people actually want it. The recent history of consumer tech is littered with high-profile and overeager attempts to get people to use conversational interfaces. Siri, which showed up on iPhones in 2011 and has since expanded across Apple’s product range, remains a useful but limited tool for completing simple tasks mostly when you can’t look at a screen or use a keyboard. Amazon has sold a ton of Alexa-based devices, but it never became a comprehensive interface for talking to the internet, just a nice way to set timers, check the weather, or control certain kinds of smart home equipment. Both are currently promising big LLM-powered updates, but they stand as gently cautionary tales about how people want to use computers, that is, in a bunch of different ways, depending on the task.

Bard Extensions are available for those who want to try them, and I have. It turns out it’s not that obvious to this longtime and frequent user of Google products what I even want out of a Google personal assistant. Its attempts to summarize my recent emails, or find documents I’ve worked on with specific collaborators, failed in crucial ways. (It found just two of dozens of documents I’d “collaborated on” with an editor, one of which I hadn’t.) At the New York Times, Kevin Roose tested it more comprehensively and came away surprised at how janky it was for a public product:

“What I found was a bit of a mess. In my testing, Bard succeeded at some simpler tasks, such as summarizing an email. But it also told me about emails that weren’t in my inbox, gave me bad travel advice and fell flat on harder analytical tasks.”

Competence issues aside, in some cases, chatting with Bard was more trouble than just doing the thing myself — it took longer, required more work on my part, and produced results that, if technically correct, were still slightly askew or incomplete. There’s also an underlying strangeness to the whole interaction. Accessing your inbox through a personified chatbot is a weird way to interact with your email much in the same way that accessing your email through another person would be weird. It’s not nearly assertive or good enough to function as CEO-grade executive assistant who takes care of your email for you. It’s more like texting with some guy who has your passwords.

These companies will presumably observe how people chat, and prefer not to chat, with their various products and adjust accordingly. Some things are better left to a button or a menu or a simple search box — plenty of things, decades later, are still best handled with the command line. Until then, we can expect chatbots to show up everywhere, as if they’d been fed the prompt: Imagine yourself as a hammer. Now, tell me some things that look like a nail. (Or, in real human terms, as if a thousand product managers at a hundred tech companies are trying to figure out what to do with their fresh OpenAI licensing deals. More chatbots? Why not!)

Microsoft’s CoPilot for Windows announcement reveals a company clearly suffering from chatbot fever. We see someone asking a chatbot, via a voice-to-text command, to play some music:

This produces a spoken response informing the user that there is a playlist called “Focus Mix” on Spotify and produces a button that allows them to … open Spotify. In other words: a slower way to arrive at the least interesting possible answer to a command.

Then, our user issues another order: Organize my windows. The chatbot says it’s “searching for the right action,” then “generating answers,” before snapping the desktop windows into a grid. This is technically interesting and could signal real accessibility improvements; LLMs offer some good news for the visually impaired. Otherwise, this is the stuff of keyboard shortcuts — there’s a physical button on a lot of computers that performs this function. If summoning a chatbot and asking it to “turn on dark mode” is the fast way for a user to access that feature, your operating system might have bigger problems. Microsoft isn’t just imagining users generally want to talk to their computers to complete tasks, here. It suggests they might want to use their voices as an interface to interact with another existing interface, which feels approximately like trying to use a computer over someone’s shoulder while they control the mouse.

Some prompts clearly reveal the potential power of LLMs. You can ask Bard to compose a gentle response to a sensitive work message you don’t know how to respond to, and it might be able to get you part of the way there. You can ask a modern chatbot to present you with a template for a résumé or cover letter for a very specific sort of job, and it will do so faster than you could Google for something similar. In cases like these, chatbots automate something that you’d rather not do, or don’t feel equipped to handle, or which you would otherwise do slowly, and use their ability to interpret the particulars of your command — gentle, short, formal — in a way saves time. There are plenty of tasks that make sense as a chat, or at least as a command — just look at how people have figured out how to use ChatGPT. There are glimmers here of truly weird and interesting possibilities that are more important than upgrades to Windows and Google Workplace.

There are plenty of cases, however, that don’t, at least for now and the foreseeable future. Roose had some issues with Bard’s travel-planning capabilities:

“I asked Bard to search my email inbox for information about a coming work trip to Europe, and look for train tickets that would get me from the airport to a business meeting in a nearby city on time.

“Bard correctly retrieved the dates of my flight, but it got the departing airport wrong. Then, it showed me a list of other flights leaving from that airport on the same day. Bard then recommended a train that would get me from the airport to my meeting on time. But when I checked the train company’s official timetables, I found no such train existed.”

Again, the shoddy results are obviously a problem, but also, What are we doing here? Bard is posing as an assistant — an entity that can do burdensome things for you but that you would have to trust to deal with second-order problems without bothering you —and is, in reality, functioning as a shoddy interface on top of a stack of other shoddy interfaces and instead returning those new problems back to you in the form of chipper conversation and errors.

Maybe we really are on the cusp of a total change to the way we interact with machines and the arrival of the long-anticipated era of truly conversational computing is imminent. (Also, lots of folks love ordering people around and issuing unrealistic commands — I’m sure that extends to machines, no problem.) It’s quite possible that, in retrospect, grumbling about chatbot interfaces will sound like command-line devotees lamenting the arrival of graphical icons and the mouse.

Or, just maybe, big tech’s frantic enthusiasm for AI will result in a few nice upgrades and a thousand weird and pointless chatbot detours, which, rather than resembling an obvious next step for human-machine interaction, look more like a regression: a return to an unreliable, shifty take on the command line, a few steps further removed from the tasks at hand. Using the early crop of LLM-powered built-for-purpose chatbots feels like acting out an expository scene intended to let the audience know that this movie is set in the crude average of all possible futures. (“Okay, computer, let’s enhance.”) Is that something anyone actually wants to see?

In the meantime, get ready. Legions of Clippys are gathering just over the horizon, and they’re armed.

More Screen Time

- GPT-4o Is OpenAI’s Plan to Win Friends and Influence People

- Why LinkedIn Now Wants You to Play Games

- TikTok Reaches for the Constitution